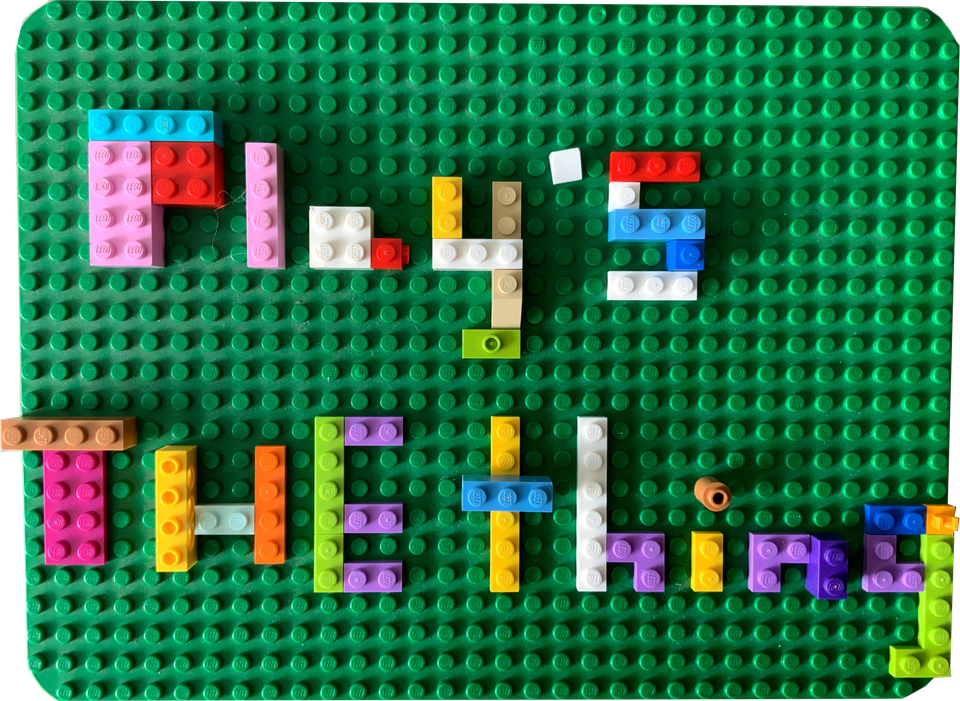

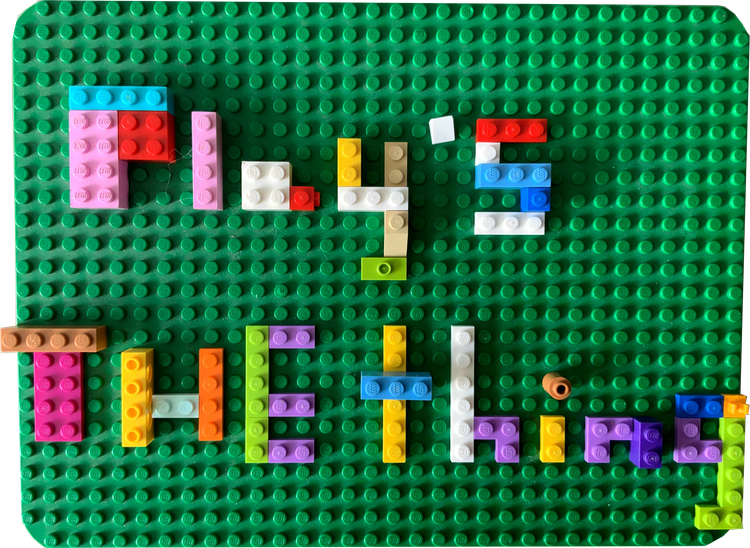

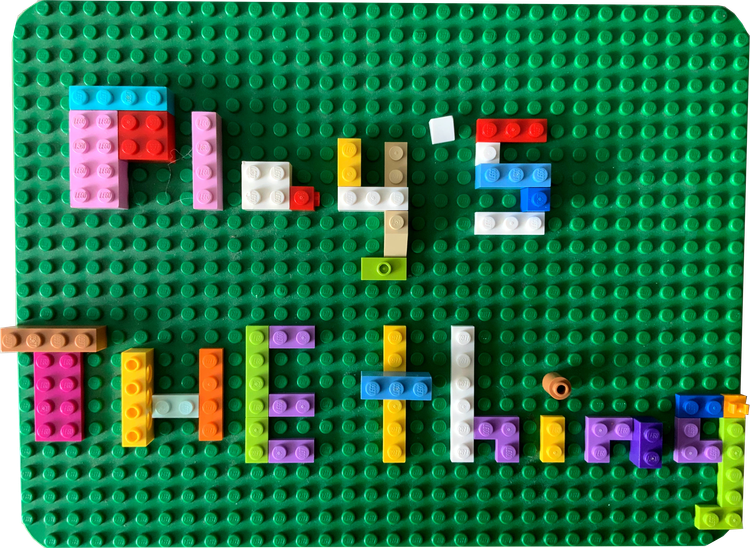

Play's The Thing: A Creative Refresh

Admit it: you thought I'd forgotten about Play's the Thing, didn't you? Admittedly, I haven't published anything under this banner since November[1] . I haven't played a Pokemon tournament since then either, and I don't know how central playing Pokemon is going to be for me going forward. Not for the kids, of course - Tommy just finished 35th at the European International Championships, their highest finish ever at that level of competition - but for me, the play-seeking hole in my being isn't Pokemon-shaped[2].

For this edition of Play's The Thing, I want to reflect a little bit on creative collaboration as a result of two wonderful experiences with two of my favorite artists in the world.

Then, I want to tell you about a little game I played while I was in New York last month.

The many facets of creative collaboration

On a recent Friday morning in London, while the kids were playing in the aforementioned Pokemon tournament, I was on the other side of the city at the Wes Anderson Archive exhibit at the Design Museum. Two days later, back in the Netherlands, I saw David Byrne perform live with a 12 piece ensemble. Both experiences felt vital in thinking about the value of play & creativity, especially with the close juxtaposition.

From a superficial perspective, the two artists Anderson & Byrne don't share much similarity: Anderson is a filmmaker, Byrne a musician; Anderson is known for a twee aesthetic and a precise visual style that is encoded in a set of rules, while Byrne is forever blending different genres into a chaotic "punk meets new wave" style. They're from different generations, different geographies, different social classes & milieus.

Despite these differences, they are two of my biggest creative influences because each of them is an archetype of what creative collaboration can be.

Byrne has a reputation for collaboration. See, for example, this very incomplete list of his "top 8" collaborations. Almost 2 decades ago, a Pitchfork writer described him as "the type who would show up to the studio if you promised them a half-empty bag of Doritos," and Byrne grabbed onto what was intended as an insult and claimed it as a badge of pride:

Beyond the reward of the bag of Doritos, why collaborate at all? One could conceivably make more money not sharing the profits — if there are any — so why collaborate if one doesn’t have to? If one can write alone, why reach out? (Some of the most financially successful songs I’ve ever written were not collaborations, for example.) And besides, isn’t it risky? Suppose you don’t get along? Suppose the other person decides to take the thing in some ugly direction?

...

Another reason to risk it is that others often have ideas outside and beyond what one would come up with oneself. To have one’s work responded to by another mind, or to have to stretch one’s own creative muscles to accommodate someone else’s muse, is a satisfying exercise. It gets us outside of our self-created boxes. When it works, the surprising result produces some kind of endorphin equivalent that is a kind of creative high. Collaborators sometimes rein in one’s more obnoxious tendencies too, which is yet another plus.

You can see it in that quote, right? The way that Byrne is a collaborator who uses collaboration as a pretext to become something of a chameleon, as he tries to inhabit "someone else's muse." And in doing it so much, he has built a muscle for how to collaborate creatively - knowing when to dial up his own sensibility, when to give way to someone else's, and when to explore how the two coexist and create something distinct in relation to each other.

The live performance he is currently touring is a celebration of creative collaboration. It's him, 3 percussionists, 4 backup vocalists & dancers, a bassist/cellist, a keyboardist, a guy who seems to play just about everything, and a guitarist. All of them are untethered; their instruments are wireless, so they all move around the stage freely. Every song is brilliantly choreographed. Every song has a video display. The live performance and the pre-recorded video fit together like hand in glove.

It took a small army to bring this to life, but it doesn't happen without Byrne. The reason his name is on the marquee is because he's the one who can get the butts in seats[3], and that almost certainly means that the controlling vision is his, but he's integrating input & ideas from all of these other collaborators...without turning the whole thing into a camel - a mishmash of different ideas that never manage to be totally coherent.

Contrast that with Wes Anderson. The first thing a visitor sees when they walk through the door into the gallery space for the Wes Anderson Archive exhibit is 2 glass cases full of journals, some of which are open to the various storyboard, snatches of dialogue, and story concepts that he has recorded throughout the years. The journals have titles on them like "The New York movie"[4], or "The train movie"[5]. Moving through the gallery, there are videos he made of himself reading lines of dialogue as a suggestion to the voice actors in his stop-motion animated films, and sometimes he films himself reading the dialogue between two characters and cuts the two videos together in the scenic composition that he wants.

His style is so defined that it became a TikTok trend, a book of still photographs that aren't from his films but look like they could be, and a pretty specific list of what "is" Wes Anderson:

- head-on camera angle

- tableau shot

- symmetrical framing (including centred framing)

- top (birds-eye) view

- still camera or foregrounded camera movement

- slow motion

- montage sequence with a soundtrack (especially rock or quirky instrumental music)

- harmonious colour palettes.

So, in short, Anderson comes to every film with a strong point of view on what he wants that film to be. He has written the screenplay, drawn the storyboards, and pulled together a cast & crew drawn from some longtime collaborators as well as some new faces - people who know how to fit within his aesthetic, and people who are learning how to.

Making a Wes Anderson movie, though, requires a lot more than the genius of Wes Anderson. What I knew conceptually going into the exhibit that I got to experience viscerally was just how material his films are: his films are made up of costumes and sets and props that are handcrafted and bespoke. His films are works of art made up of aggregations of works of art - they often feature books that don't exist in the real world, paintings, sculptures, custom wallpaper, bejeweled knives. The films lend themselves to building their own microcosms of worlds.

The Wes Anderson approach to creative collaboration is to lay out a canvas that is already chock full of precise detail & point out where there is negative space that he needs others to fill in.

It would be fair to wonder whether his collaborators experience this as collaboration. There are plenty of directors who were maniacally focused on bringing their singular vision to life in ways that became toxic, even traumatic. In Anderson's case, however, it's the fact that he has such a large group of regular collaborators that give weight to the idea that he is someone that people want to work with, that they see bring out the best in them - because of the exacting standard that he defines.

The Byrne archetype and the Anderson archetype of creative collaboration, like the men themselves, are distinctly different from each other - though not opposed. In both cases, the methods are creating a meta-form of play[6]. In Homo Ludens, Huizinga identifies the magic circle as one of the defining elements of play[7]: the space - real or imagined - that you enter into where everyone inside understands that they're engaging in a construct together. Byrne and Anderson are both creating a magic circle for their audiences, but the way that they create that magic circle is by also creating a different magic circle for their collaborators. The way you play David Byrne creative collaboration follows a different logic than than the way that you play Wes Anderson creative collaboration. Not every work of art emerges from within a magic circle, and while these two are not the only kinds of magic circle, they are two that I'm grateful to have been able to play in myself.

A little game I played on my recent trip to New York

For me, New York City might as well be a massive gameboard for a game called "The Paradox of Choice." When I travel with the kids, I'm constrained by their dietary needs. When I travel to most American cities, I'm constrained by the fact that I don't want to spend my time riding in the back of a car or driving. If I'm in New York by myself, then neither of those constraints exist. Nor do constraints like "well, what kind of food is this city known for?"

Related: I am a person who is easily sucked into maps. I make maps of every city I visit so that I know about the places I want to check out and where they are in proximity to each other and to the places that I need to be. But in New York, the density of options is such that a map can quickly become exhausting. Deciding something simple like where to eat can become such a production.

So I made my dining decisions on this last trip to New York into a game of constraints. The constraints were:

- You can eat at places that people have recommended to you.

- You can eat at places that you see while you're wandering around.

Those constraints incentivized 2 kinds of behavior: - the first incentivized being social. If I was going to meet up with people, I could ask them to suggest a place. If I had friends who I knew had been in the city recently, I could ask for their recommendations.

- the second incentivized walking around and getting off of the beaten path[8]. If I wanted to find something interesting, I had to go out looking. This one also meant I had to be attentive to my own intuition around what I was drawn to (or not).

The normal game of eating in New York is about trying to find the best food. My version of the game was about finding places to connect with people. And, because it's New York, I still ended up eating really well.

Coming soon...

I swear I'm going to write something about my time in Singapore. It's coming together slowly. Nerd Notes subscribers this month are getting a little Read Me Like A Book easter egg, and some nostalgia for the days of freeware & shareware.

- And when I did, I accidentally titled it Pursuit of Play. Oops.

- Am I enjoying imagining a hole the size and shape of various Pokemon? I am.

- and, frequently, out of seats to dance

- (The Royal Tenenbaums)

- (Darjeeling Limited)

- You were wondering how I was going to connect it, huh?

- I told you I was going to harp on this book for a long time.

- The huge blizzard that hit the city while I was there did not really help on this front.

Member discussion