The secret is in the circle

A couple months ago, I wrote about something my coach had said to me that was revelatory...and as I was writing it I felt a little bit of a twinge - not of guilt, but of something like painful awareness. Here's the thing: for most of my own professional life, I haven't had anything like a coach or a mentor. While I feel really fortunate to have a great coach now (and a solid sounding board of mentor-type people), I'm not offering this as a lament, because I never felt like I was missing out. There's an important reason why, a super critical piece of my own growth that I think is available and accessible to anyone who wants to put in a little bit of legwork...and I don't think we talk about it enough. I've always had a circle of badass peers.

Before I dig in any further, though, let me just acknowledge and appreciate two of those badass peers who helped me think through this and sort out my ideas. Big shout outs to Theo and Yusuf.

And, continuing with the experiment, if you’d prefer to listen to this you can do it here.

So, um, did you say "circle of badass peers"?

Yes, correct. That's what I said.

Right, OK. What is that exactly?

Oh yeah, I suppose it does merit an explanation. Maybe it's easiest if we start with what it isn't. There are 4 things - each of which is also valuable - that your badass peers are not; while at times they may do things that are similar to these roles they do not occupy these roles:

They're not mentors - a mentor is someone who has walked a pathway similar to the one that you are on, and they're usually quite a bit further along on that pathway than you are. They take an interest in you; they usually want to support your growth in some way. A good mentor is an incredible person to have in your corner...but I see 3 main drawbacks with mentors:

The mentoring relationship usually has a one way power dynamic;

the mentor tends to choose you rather than vice versa;

and it's hard to tell if you have a bad mentor.

They're not coaches - a coach is a lot like a mentor. The main difference, and it's a big one, is that you tend to compensate your coach. This eliminates 2 of the 3 drawbacks to mentors (you get some choice, and you usually know what you're trying to get and whether you're getting it thus can weed out bad coaches) and mitigates the 3rd (because you have the power of choice, it mediates the dynamic a bit). If you want to get in depth on what great coaching can be, Atul Gawande had an amazing article in the New Yorker years ago. There are, however, 2 main drawbacks with coaches:

that whole compensation bit is something that can make coaches inaccessible,

and there's the whole Matthew principle where the best coaches choose who they make themselves available to - usually based on who already shows great promise.

They're not role models - a role model is a more high profile mentor who you don't have direct access to. I love Craig Mod's recent essay on role models. We're living in a golden age for tapping into the wisdom of role models; there's an absurd amount of newsletters, videos, online classes, and so on for any interest you may have no matter how niche. That's unequivocally awesome. Nonetheless, there are drawbacks:

first, the challenge that often comes from abundance of figuring out what is actually good;

second, the actual reality of expert blind spots...experts often leave out a ton when they narrate how they go about something, because so much has become second nature to them. That lack of direct access means you can't probe, inquire, and challenge.

third, unlike coaches and mentors, you don't get direct feedback from role models. That gulf between what you aspire to do and what you can actually do is very difficult to cross on your own.

They're not friends - or, at the very least they're not necessarily friends. They're not inherently friends. This is probably where there's the most room for overlap, but make no mistake: your badass peers do not need to be your friends. Your friends are people you enjoy hanging out with and doing whatever you find fun, they support you through all sorts of personal stuff. As I mentioned in 40 for 40, you can have a pretty good friendship based on the foundation of being able to make each other laugh. There's a good chance that over time badass peers become friends, and in the short term you need to at least be friendly with your badass peers. In the beginning, though, not the same as friends. The explanatory example to illustrate this: when I moved back to the US from overseas and was getting my footing again, my friends offered me a bed to sleep in until I found my own place; my badass peers offered me projects to collaborate on until I found a job.

That's a lot of words to spend not answering the question.

I once got some media training, and the biggest thing I remember from it is, "don't answer the question you were asked. Answer the question you want to answer."

Aren't you also the one writing these questions?

Fair enough.

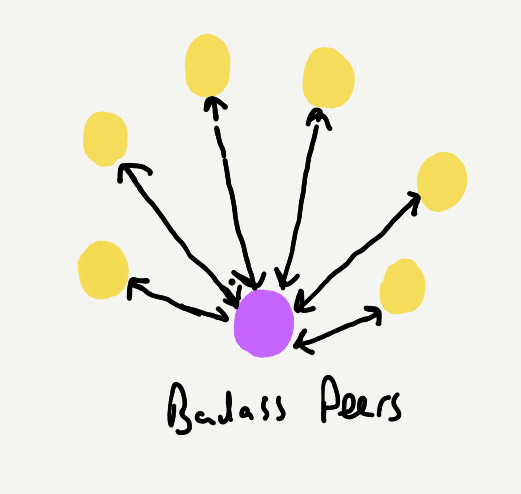

So here's what badass peers are: they are people doing work that you find interesting and relevant to your own work who are at a similar enough level of experience that you can help them make their work better, and they can do the same for you.

They don't necessarily work in the same field as you. They don't necessarily have the same goals or aspirations as you. But there's some unifying reason that you both want to support each other. Maybe you've got similar methods, maybe you're asking similar questions in different spaces. Maybe you're both way too into steampunk?

If you stop and think for a quick minute, I bet you can come up with a couple of these people in your life right now. Possibly even as many as a handful.

The secret isn't the individual relationships - the secret is the circle.

You're going to make me ask about the cryptic phrase, "the secret is the circle," aren't you?

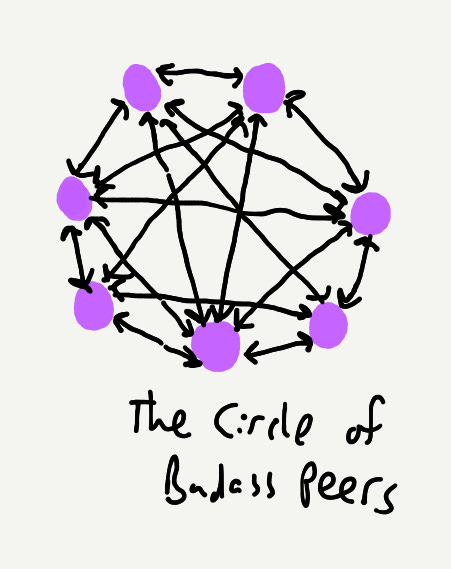

I'm so glad you asked. If you only have 1 or 2 of these relationships, it's a lot to put on them to expect them to really nurture your growth. Even if you have 1 or 2 that are more fertile than others, you really want a somewhat denser web of connections. I think the ideal number is somewhere around half a dozen. It's enough that you aren't putting too much strain on any one strand of relationship.

At the lowest maintenance version of this, you have a collection of badass peers - multiple people that you have a direct connection with and you are mutually supporting each other's work.

If you don't have this, then even just aspiring to create this structure for yourself is a great starting point. If you have this, then you probably already recognize that it's a very good thing...but it's not the best thing. The drawback in this structure is that all of the relationships have only 1 link.

To create a circle of badass peers, you want to create links between all the nodes.

In the same way that the image just looks a whole lot more complex, when you have a circle of badass peers everyone's work takes on a new level of richness and depth. Often, it's also where you see people taking bolder, more ambitious steps - because they get more diversity of perspective, more rigor of discourse, and also the confidence that comes from knowing that you've got people on your side. The other people here have enough overlap with each other that they have enough of a common frame of reference, but they also have enough difference that they introduce new ways of thinking, seeing, and creating.

In my early twenties, my circle of badass peers was me (ostensibly some kind of journalist/playwright), a painter, a massage therapist, a philosopher, a photographer, and a handyman/sculptor. All of us had some motivation to create new things, all of us were kind of activist-y in certain ways, and all of us shared a kind of wabi-sabi aesthetic. That was enough to connect us, and that pushed each of our work into directions we never would have considered and led us into shared thematic explorations. Reader, I tell you it was rad.

And - this is critical - making this happen takes some energy, a bit of legwork. You have to put energy both into the initial activation of this circle, and you have to put energy into maintaining the circle.

It isn't actually as hard as it sounds. Activation is a matter of a simple willingness to gather people - if you know who your people are, find an excuse to bring them together so that they start bouncing off of each other. Throw a dinner party, form a book group. Something that puts them in a space and exposes the reason that they might become badass peers.

Give it time. It won't happen after just one encounter. That's where the value of a shared place comes in - if you can establish a lowkey routine for finding a reason to connect and congregate, then people will pop in & out and build more shared context. Sometimes this happens naturally - in more than one instance, my closest circle of badass peers have been people who worked at the same company as me. I've also had the times when I have just let my people know, "hey, I'm going to work from this cafe every Wednesday at 7pm. Come by if you want to work too."

(By the way, you may be reading this and recognizing that someone in your life - wittingly or unwittingly - is inviting you into their own circle of badass peers.)

Now, there is an important caveat: not all of the links will be equally strong and you shouldn't expect them to be. Some links will be tenuous, some may go weaker (or stronger) for a period of time.

And another one: if this sounds pretty organic and hard to actively monitor and assign performance metrics to, I think that's basically true. In fact, even if there was a way to do that I'd be wary of it. If the circle of badass peers becomes transactional, the circle will break down. It needs relationship at it's core, and to the extent you have to force that it may just not be the right group of people. That's OK...don't force it, just make room for other people. Eventually, the pieces will fit together.

Maybe it's time to wrap it up?

Right. Of course.

I've been thinking about this for months. It doesn't have to do with education or product development, but I think it does have to do with that impulse and desire to create, and make, and build things. Over time I've moved in & out of various circles of badass peers, and I really can't imagine where my own work would be without those people and those relationships. I want that for everyone, and I particularly love it because it isn't hierarchical in nature - it's collective.

I wasn't sure how to end this, but then over the weekend a wonderful thing happened: Everything Everywhere All At Once won a whole bunch of Oscars. Everything I have encountered about the making of that film seems to capture the pinnacle of what is possible when you have a great circle of badass peers, and in their acceptance speech for Best Director, Daniel Kwan said something that I felt viscerally, so I'll leave you today with that:

I know every director agrees with me when I say a director is nothing without their incredible cast and crew. If our movie has greatness and genius, it is only because they have greantess and genius flowing through their hearts and souls and minds, and they gave that precious gift to our film. The world is opening up to the fact that genius does not stem from individuals like us onstage, but rather genius emerges from the collective. We are all products of our context.

Go build your circle.